Convolutional neural networks (convnets) are all the rage right now. Training a convnet on any reasonably sized dataset is very computationally intensive, so GPU acceleration is indispensible. In this post I’ll show how you can use the blazing fast convolution implementation from Alex Krizhevsky’s cuda-convnet in Theano.

As an example, I’ll also show how the LeNet deep learning tutorial on convolutional neural networks can be modified to use this convolution implementation instead of Theano’s own, resulting in a 3x speedup.

Introduction

Quite a few libraries offering GPU-accelerated convnet training have sprung up in recent years: cuda-convnet, Caffe and Torch7 are just a few. I’ve been using Theano for anything deep learning-related, because it offers a few advantages:

- it allows you to specify your models symbolically, and compiles this representation to optimised code for both CPU and GPU. It (almost) eliminates the need to deal with implementation details;

- it does symbolic differentiation: given an expression, it can compute gradients for you.

The combination of these two advantages makes Theano ideal for rapid prototyping of machine learning models trained with gradient descent. For example, if you want to try a different objective function, just change that one line of code where you define it, and Theano takes care of the rest. No need to recompute the gradients, and no tedious optimisation to get it to run fast enough. This is a huge time saver.

Performance vs. flexibility

Theano comes with a 2D convolution operator out of the box, but its GPU implementation hasn’t been the most efficient for a while now, and other libraries have surpassed it in performance. Unfortunately, they don’t typically offer the flexibility that Theano offers.

Luckily, we no longer need to choose between performance and flexibility: the team behind pylearn2, a machine learning research library built on top of Theano, has wrapped the blazing fast convolution implementation from Alex Krizhevsky’s cuda-convnet library so that it can be used in Theano.

This wrapper can be used directly from Theano, without any dependencies on other pylearn2 components. It is not a drop-in replacement for Theano’s own conv2d, and unfortunately its documentation is limited, so in this post I’m going to try and describe how to use it. I’ve seen speedups of 2x-3x after replacing Theano’s own implementation with this one in some of my own code, so if you’re doing convolutions in Theano this is definitely worth trying out.

Why not just use cuda-convnet? cuda-convnet is an impressive piece of software, and while it does implement a lot of state-of-the-art techniques, it does not offer the same degree of flexibility that Theano offers.

Why not just use pylearn2 then? Although pylearn2 is specifically aimed at researchers, it has a fairly steep learning curve due to its emphasis on modularity and code reuse. Of course these are desirable qualities, but when writing research code, I personally prefer to keep the cognitive overhead minimal, and using Theano affords me that luxury.

Requirements

For this post I will assume that Python, numpy and Theano are installed and working, and that you have access to a CUDA-enabled GPU.

Make sure to configure Theano to use the GPU: set device=gpu and floatX=float32 in your .theanorc file, or in the THEANO_FLAGS environment variable (more info in the Theano documentation).

You will also need to get pylearn2:

git clone git://github.com/lisa-lab/pylearn2.gitAdd the resulting directory to your PYTHONPATH, so the pylearn2 module can be imported:

export PYTHONPATH=$PYTHONPATH:/path/to/pylearn2Detailed installation instructions can be found in the pylearn2 documentation. However, note that some dependencies (PIL, PyYAML) will not be necessary if you are only going to use the cuda-convnet wrappers.

Usage

Overview

Assume the following imports and definitions:

import theano.tensor as T

input = T.tensor4('input')

filters = T.tensor4('filters')We have defined two 4-tensors: one for the input data, and one for the filters that will be convolved with it. A 2D convolution in Theano is normally implemented as follows:

from theano.tensor.nnet import conv

out = conv.conv2d(input, filters, filter_shape=filter_shape,

image_shape=image_shape)To use the cuda-convnet wrappers from pylearn2 instead, use the following code:

from pylearn2.sandbox.cuda_convnet.filter_acts import FilterActs

from theano.sandbox.cuda.basic_ops import gpu_contiguous

conv_op = FilterActs()

contiguous_input = gpu_contiguous(input)

contiguous_filters = gpu_contiguous(filters)

out = conv_op(contiguous_input, contiguous_filters)This is a little wordier. An interesting peculiarity is that the FilterActs wrapper needs to be instantiated before it can be used in a Theano expression (line 4).

Next, we need to make sure that the inputs are laid out correctly in memory (they must be C-contiguous arrays). This is what the gpu_contiguous helper function achieves (lines 5 and 6). It will make a copy of its input if the layout is not correct. Otherwise it does nothing. Wrapping the inputs in this way is not always necessary, but even if it isn’t, the performance overhead seems to be minimal anyway, so I recommend always doing it just to be sure.

The convolution can then be applied to the contiguous inputs (line 7).

Different input arrangement: bc01 vs. c01b

An important difference with Theano’s own implementation is that FilterActs expects a different arrangement of the input. Theano’s conv2d expects its input to have the following shapes:

- input:

(batch size, channels, rows, columns) - filters:

(number of filters, channels, rows, columns)

In pylearn2, this input arrangement is referred to as bc01. In cuda-convnet, the following shapes are expected instead:

- input:

(channels, rows, columns, batch_size) - filters:

(channels, rows, columns, number of filters)

This is referred to as c01b.

If you have an existing codebase which assumes the bc01 arrangement everywhere, the simplest way to deal with this is to use Theano’s dimshuffle method to change the order of the dimensions as appropriate:

conv_op = FilterActs()

input_shuffled = input.dimshuffle(1, 2, 3, 0) # bc01 to c01b

filters_shuffled = filters.dimshuffle(1, 2, 3, 0) # bc01 to c01b

contiguous_input = gpu_contiguous(input_shuffled)

contiguous_filters = gpu_contiguous(filters_shuffled)

out_shuffled = conv_op(contiguous_input, contiguous_filters)

out = out_shuffled.dimshuffle(3, 0, 1, 2) # c01b to bc01However, this may incur a performance penalty because it requires making a copy of the data. This negates some of the performance gained by using the cuda-convnet implementation in the first place.

Contrary to what the Theano documentation says, the negative effect on performance of adding these dimshuffle calls is not necessarily that profound, in my experience. Nevertheless, using the c01b arrangement everywhere will result in faster execution.

Convolution vs. correlation

The code fragment above still isn’t a drop-in replacement for Theano’s conv2d, because of another subtle difference: FilterActs technically implements a correlation, not a convolution. In a convolution, the filters are flipped before they are slided across the input. In correlation, they aren’t. So to perform an operation that is equivalent to Theano’s conv2d, we have to flip the filters manually (line 4):

conv_op = FilterActs()

input_shuffled = input.dimshuffle(1, 2, 3, 0) # bc01 to c01b

filters_shuffled = filters.dimshuffle(1, 2, 3, 0) # bc01 to c01b

filters_flipped = filters_shuffled[:, ::-1, ::-1, :] # flip rows and columns

contiguous_input = gpu_contiguous(input_shuffled)

contiguous_filters = gpu_contiguous(filters_flipped)

out_shuffled = conv_op(contiguous_input, contiguous_filters)

out = out_shuffled.dimshuffle(3, 0, 1, 2) # c01b to bc01However, when the filters are being learned from data, it doesn’t really matter how they are oriented, as long as they are always oriented in the same way. So in practice, it is rarely necessary to flip the filters.

Limitations

FilterActs has several limitations compared to conv2d:

- The number of channels must be even, or less than or equal to 3. If you want to compute the gradient, it should be divisible by 4. If you’re training a convnet, that means valid numbers of input channels are 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 12, 16, …

- Filters must be square, the number of rows and columns should be equal. For images, square filters are usually what you want anyway, but this can be a serious limitation when working with non-image data.

- The number of filters must be a multiple of 16.

- All minibatch sizes are supported, but the best performance is achieved when the minibatch size is a multiple of 128.

- Only “valid” convolutions are supported. If you want to perform a “full” convolution, you will need to use zero-padding (more on this later).

FilterActsonly works on the GPU. You cannot run your Theano code on the CPU if you use it.

Tuning the time-memory trade-off with partial_sum

When instantiating FilterActs, we can specify the partial_sum argument to control the trade-off between memory usage and performance. From the cuda-convnet documentation:

partialSum is a parameter that affects the performance of the weight gradient computation. It’s a bit hard to predict what value will result in the best performance (it’s problem-specific), but it’s worth trying a few. Valid values are ones that divide the area of the output grid in this convolutional layer. For example if this layer produces 32-channel 20x20 output grid, valid values of partialSum are ones which divide 20*20 = 400.

By default, partial_sum is set to None, which is the most conservative setting in terms of memory usage. To speed things up, the value can be tuned as described above, at the expense of higher memory usage. In practice, setting it to 1 tends to work very well (and it’s always a valid value, regardless of the size of the output grid):

conv_op = FilterActs(partial_sum=1)

contiguous_input = gpu_contiguous(input)

contiguous_filters = gpu_contiguous(filters)

out = conv_op(contiguous_input, contiguous_filters)I recommend setting partial_sum to 1 and leaving it at that. In most cases this will work well enough, and it saves you the trouble of having to recompute the divisors of the output grid area every time you change the filter size. I have observed only very minimal performance gains from optimising this setting.

If you don’t have a lot of GPU memory to spare, leaving this setting at None will reduce performance, but it will likely still be quite a bit faster than Theano’s implementation.

Strided convolutions

Although Theano’s conv2d allows for convolutions with strides different from 1 through the subsample parameter, the performance tends to be a bit disappointing, in my experience. FilterActs has much better support for strided convolutions. The stride argument can be specified when instantiating FilterActs (it defaults to 1):

conv_op = FilterActs(partial_sum=1, stride=2)

contiguous_input = gpu_contiguous(input)

contiguous_filters = gpu_contiguous(filters)

out = conv_op(contiguous_input, contiguous_filters)stride should be an integer, not a tuple, so this implies that the stride has to be the same in both dimensions, just like the filter size.

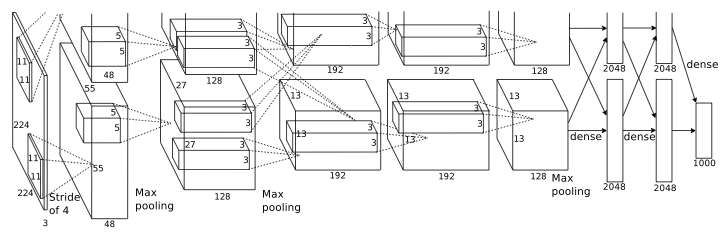

This is very useful for large input images, since it is a lot cheaper than computing a full convolution and then pooling the result. In the ImageNet classification paper, Krizhevsky et al. used a convolution with stride 4 in the first layer of their convnet.

Zero-padding

FilterActs supports another optional argument pad, which defaults to 0. Setting this to another value p will implicitly pad the input with a border of p zeros on all sides. This does not use extra memory, so it is much cheaper than adding the padding yourself.

This argument can be used to implement a “full” convolution instead of a “valid” one, by padding the input with filter_size - 1 zeros:

conv_op = FilterActs(partial_sum=1, pad=filter_size - 1)

contiguous_input = gpu_contiguous(input)

contiguous_filters = gpu_contiguous(filters)

out = conv_op(contiguous_input, contiguous_filters)Let n be the input size and f the filter size, then padding the input with f - 1 zeros on all sides changes the input size to n + 2f - 2. Applying the convolution then results in an output size of (n + 2f - 2) - (f - 1) = n + f - 1, which corresponds to a “full” convolution.

Max-pooling

In addition to FilterActs, there is also a MaxPool wrapper. In Theano, you would implement 2D max-pooling as follows:

from theano.tensor.signal import downsample

out = downsample.max_pool_2d(input, ds=(2, 2))To use the wrappers instead:

from pylearn2.sandbox.cuda_convnet.pool import MaxPool

from theano.sandbox.cuda.basic_ops import gpu_contiguous

pool_op = MaxPool(ds=2, stride=2)

contiguous_input = gpu_contiguous(input)

out = pool_op(contiguous_input)Once again we need to ensure C-contiguousness with gpu_contiguous. The input should be in c01b format as before.

Note that the MaxPool op accepts both a ds and a stride argument. If you set both to the same value, you get traditional max-pooling. If you make ds larger than stride, you get overlapping pooling regions. This was also used in the ImageNet classification paper mentioned earlier: they used a pool size of 3 and a stride of 2, so each pool overlaps with the next by 1 pixel.

ds and stride should be integers, not tuples, so this implies that pooling regions should be square, and the strides should be the same in both dimensions.

Another important limitation is that MaxPool only works for square input images. No such limitation applies for FilterActs. If you run into problems with this, you could use FilterActs in combination with Theano’s own max_pool_2d implementation - it’s a bit slower this way, but max-pooling is not the bottleneck in a convnet anyway, the convolutions are.

Other wrappers

There are a few other wrappers for cuda-convnet code in pylearn2: ProbMaxPool (probabilistic max-pooling, Lee et al. 2009), StochasticMaxPool, WeightedMaxPool (stochastic max-pooling, Zeiler et al. 2013) and CrossMapNorm (cross-channel normalisation, Krizhevsky et al., 2012). I will not discuss these in detail, but many of the same remarks and restrictions apply.

More information about these wrappers can be found in the pylearn2 documentation. Any missing information can usually be found in the cuda-convnet documentation.

The stochastic max-pooling implementation is not from cuda-convnet itself, but was built on top of it. As a result, it’s actually pretty slow. If you need this, implementing stochastic max-pooling yourself in Theano may be faster.

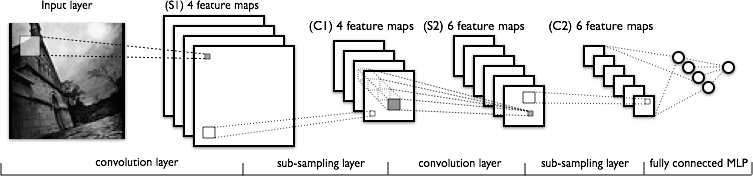

Modifying the LeNet deep learning tutorial

To wrap up this post, let’s modify the deep learning tutorial on convolutional neural networks to use these wrappers instead of Theano’s own implementations. The tutorial explains how to train a convolutional neural network on the MNIST dataset with Theano. If you’re not familiar with it, have a look at the tutorial before continuing.

You can download the necessary files below (place them in the same directory):

All the code we’ll have to modify is in convolutional_mlp.py. First, let’s add and replace the necessary imports. In what follows, all replaced code is commented. On line 34:

# from theano.tensor.signal import downsample

# from theano.tensor.nnet import conv

from theano.sandbox.cuda.basic_ops import gpu_contiguous

from pylearn2.sandbox.cuda_convnet.filter_acts import FilterActs

from pylearn2.sandbox.cuda_convnet.pool import MaxPoolNext, we’ll need to modify the LeNetConvPoolLayer class to use FilterActs and MaxPool instead. On line 88:

# convolve input feature maps with filters

# conv_out = conv.conv2d(input=input, filters=self.W,

# filter_shape=filter_shape, image_shape=image_shape)

input_shuffled = input.dimshuffle(1, 2, 3, 0) # bc01 to c01b

filters_shuffled = self.W.dimshuffle(1, 2, 3, 0) # bc01 to c01b

conv_op = FilterActs(stride=1, partial_sum=1)

contiguous_input = gpu_contiguous(input_shuffled)

contiguous_filters = gpu_contiguous(filters_shuffled)

conv_out_shuffled = conv_op(contiguous_input, contiguous_filters)And on line 92:

# downsample each feature map individually, using maxpooling

# pooled_out = downsample.max_pool_2d(input=conv_out,

# ds=poolsize, ignore_border=True)

pool_op = MaxPool(ds=poolsize[0], stride=poolsize[0])

pooled_out_shuffled = pool_op(conv_out_shuffled)

pooled_out = pooled_out_shuffled.dimshuffle(3, 0, 1, 2) # c01b to bc01Note that we’re using plenty of dimshuffle calls here, so we can keep using the bc01 input arrangement in the rest of the code and no further changes are necessary. Also note that we did not flip the filters: there is no point because the weights are being learned.

Just one more change is necessary: the tutorial specifies a convnet with two convolutional layers, with 50 and 20 filters respectively. This is not going to work with FilterActs, which expects the number of filters to be a multiple of 16. So we’ll have to change the number of filters on line 106:

# def evaluate_lenet5(learning_rate=0.1, n_epochs=200,

# dataset='mnist.pkl.gz',

# nkerns=[20, 50], batch_size=500):

def evaluate_lenet5(learning_rate=0.1, n_epochs=200,

dataset='mnist.pkl.gz',

nkerns=[32, 64], batch_size=500):Now it should work. You can download the modified file here (place it in the same directory):

Running the unmodified code for 50 epochs with 32 and 64 filters respectively takes 110 minutes on the GeForce GT 540M in my laptop:

Optimization complete.

Best validation score of 1.120000 % obtained at iteration 5000,

with test performance 1.000000 %

The code for file convolutional_mlp.py ran for 109.47mWith FilterActs and MaxPool instead of the Theano implementation, it only takes 34 minutes:

Optimization complete.

Best validation score of 1.120000 % obtained at iteration 5000,

with test performance 0.940000 %

The code for file convolutional_mlp_cc.py ran for 33.76mA 3.2x speedup!

On a workstation with a GeForce GTX 680, the unmodified code takes 13.15 minutes for 50 epochs. Using FilterActs, it takes 4.75 minutes, which amounts to a 2.7x speedup.