Diffusion models appear to come in many shapes and forms. If you pick two random research papers about diffusion and look at how they describe the model class in their respective introductions, chances are they will go about it in very different ways. This can be both frustrating and enlightening: frustrating, because it makes it harder to spot relationships and equivalences across papers and implementations – but also enlightening, because these various perspectives each reveal new connections and are a breeding ground for new ideas. This blog post is an overview of the perspectives on diffusion I’ve found useful.

Last year, I wrote a blog post titled “diffusion models are autoencoders”. The title was tongue-in-cheek, but it highlighted a close connection between diffusion models and autoencoders, which I felt had been underappreciated up until then. Since so many more ML practitioners were familiar with autoencoders than with diffusion models, at the time, it seemed like a good idea to try and change that.

Since then, I’ve realised that I could probably write a whole series of blog posts, each highlighting a different perspective or equivalence. Unfortunately I only seem to be able to produce one or two blog posts a year, despite efforts to increase the frequency. So instead, this post will cover all of them at once in considerably less detail – but hopefully enough to pique your curiosity, or to make you see diffusion models in a new light.

This post will probably be most useful to those who already have at least a basic understanding of diffusion models. If you don’t count yourself among this group, or you’d like a refresher, check out my earlier blog posts on the topic:

- Diffusion models are autoencoders

- Guidance: a cheat code for diffusion models

- Diffusion language models

Before we start, a disclaimer: some of these connections are deliberately quite handwavy. They are intended to build intuition and understanding, and are not supposed to be taken literally, for the most part – this is a blog post, not a peer-reviewed research paper.

That said, I welcome any corrections and thoughts about the ways in which these equivalences don’t quite hold, or could even be misleading. Feel free to leave a comment, or reach out to me on Twitter (@sedielem) or Threads (@sanderdieleman). If you have a different perspective that I haven’t covered here, please share it as well.

Alright, here goes (click to scroll to each section):

- Diffusion models are autoencoders

- Diffusion models are deep latent variable models

- Diffusion models predict the score function

- Diffusion models solve reverse SDEs

- Diffusion models are flow-based models

- Diffusion models are recurrent neural networks

- Diffusion models are autoregressive models

- Diffusion models estimate expectations

- Discrete and continuous diffusion models

- Alternative formulations

- Consistency

- Defying conventions

- Closing thoughts

- Acknowledgements

- References

Diffusion models are autoencoders

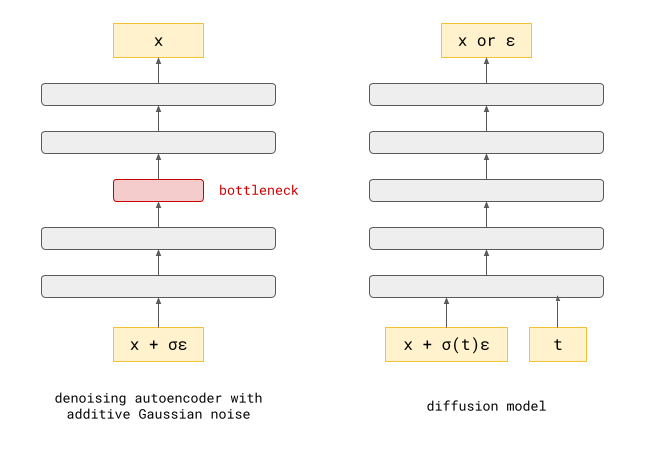

Denoising autoencoders are neural networks whose input is corrupted by noise, and they are tasked to predict the clean input, i.e. to remove the corruption. Doing well at this task requires learning about the distribution of the clean data. They have been very popular for representation learning, and in the early days of deep learning, they were also used for layer-wise pre-training of deep neural networks1.

It turns out that the neural network used in a diffusion model usually solves a very similar problem: given an input example corrupted by noise, it predicts some quantity associated with the data distribution. This can be the corresponding clean input (as in denoising autoencoders), the noise that was added, or something in between (more on that later). All of these are equivalent in some sense when the corruption process is linear, i.e., the noise is additive: we can turn a model that predicts the noise into a model that predicts the clean input, simply by subtracting its prediction from the noisy input. In neural network parlance, we would be adding a residual connection from the input to the output.

There are a few key differences:

-

Denoising autoencoders often have some sort of information bottleneck somewhere in the middle, to learn a useful representation of the input whose capacity is constrained in some way. The denoising task itself is merely a means to an end, and not what we actually want to use the models for once we’ve trained them. The neural networks used for diffusion models don’t typically have such a bottleneck, as we are more interested in their predictions, rather than the internal representations they construct along the way to be able to make those predictions.

-

Denoising autoencoders can be trained with a variety of types of noise. For example, parts of the input could be masked out (masking noise), or we could add noise drawn from some arbitrary distribution (often Gaussian). For diffusion models, we usually stick with additive Gaussian noise because of its helpful mathematical properties, which simplify a lot of operations.

-

Another important difference is that denoising autoencoders are usually trained to deal only with noise of a particular strength. In a diffusion model, we have to be able to make predictions for inputs with a lot of noise, or with very little noise. The noise level is provided to the neural network as an extra input.

As mentioned, I’ve already discussed this relationship in detail in a previous blog post, so check that out if you are keen to explore this connection more thoroughly.

Diffusion models are deep latent variable models

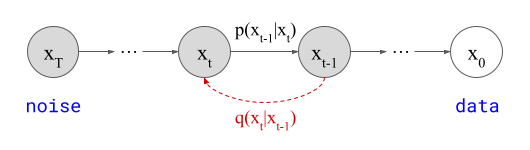

Sohl-Dickstein et al. first suggested using a diffusion process to gradually destroy structure in data, and then constructing a generative model by learning to reverse this process in a 2015 ICML paper2. Five years later, Ho et al. built on this to develop Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models or DDPMs3, which formed the blueprint of modern diffusion models along with score-based models (see below).

In this formulation, represented by the graphical model above, \(\mathbf{x}_T\) (latent) represents Gaussian noise and \(\mathbf{x}_0\) (observed) represents the data distribution. These random variables are bridged by a finite number of intermediate latent variables \(\mathbf{x}_t\) (typically \(T=1000\)), which form a Markov chain, i.e. \(\mathbf{x}_{t-1}\) only depends on \(\mathbf{x}_t\), and not directly on any preceding random variables in the chain.

The parameters of the Markov chain are fit using variational inference to reverse a diffusion process, which is itself a Markov chain (in the other direction, represented by \(q(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t-1})\) in the diagram) that gradually adds Gaussian noise to the data. Concretely, as in Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)45, we can write down an Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO), a bound on the log likelihood, which we can maximise tractably. In fact, this section could just as well have been titled “diffusion models are deep VAEs”, but I’ve already used “diffusion models are autoencoders” for a different perspective, so I figured this might have been a bit confusing.

We know \(q(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_{t-1})\) is Gaussian by construction, but \(p(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t)\), which we are trying to fit with our model, need not be! However, as long as each individual step is small enough (i.e. \(T\) is large enough), it turns out that we can parameterise \(p(\mathbf{x}_{t-1} \mid \mathbf{x}_t)\) as if it were Gaussian, and the approximation error will be small enough for this model to still produce good samples. This is kind of surprising when you think about it, as during sampling, any errors may accumulate over \(T\) steps.

Full disclosure: out of all the different perspectives on diffusion in this blog post, this is probably the one I understand least well. Sort of ironic, given how popular it is, but variational inference has always been a little bit mysterious to me. I will stop here, and mostly defer to a few others who have described this perspective in detail (apart from the original DDPM paper, of course):

- “Diffusion Models as a kind of VAE” by Angus Turner

- Jakub Tomczak’s blog post on DDPMs

- Lilian Weng’s blog post on diffusion models (connects multiple perspectives)

- Alex Alemi’s blog post about the variational diffusion loss

Diffusion models predict the score function

Most likelihood-based generative models parameterise the log-likelihood of an input \(\mathbf{x}\), \(\log p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta)\), and then fit the model parameters \(\theta\) to maximise it, either approximately (as in VAEs) or exactly (as in flow-based models or autoregressive models). Because log-likelihoods represent probability distributions, and probability distributions have to be normalised, this usually requires some constraints to ensure all possible values for the parameters \(\theta\) yield valid distributions. For example, autoregressive models have causal masking to ensure this, and most flow-based models require invertible neural network architectures.

It turns out there is another way to fit distributions that neatly sidesteps this normalisation requirement, called score matching6. It’s based on the observation that the so-called score function, \(s_\theta(\mathbf{x}) := \nabla_\mathbf{x} \log p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta)\), is invariant to the scaling of \(p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta)\). This is easy to see:

\[\nabla_\mathbf{x} \log \left( \alpha \cdot p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta) \right) = \nabla_\mathbf{x} \left( \log \alpha + \log p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta) \right)\] \[= \nabla_\mathbf{x} \log \alpha + \nabla_\mathbf{x} \log p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta) = 0 + \nabla_\mathbf{x} \log p(\mathbf{x} \mid \theta) .\]Any arbitrary scale factor applied to the probability density simply disappears. Therefore, if we have a model that parameterises a score estimate \(\hat{s}_\theta(\mathbf{x})\) directly, we can fit the distribution by minimising the score matching loss (instead of maximising the likelihood directly):

\[\mathcal{L}_{SM} := \left( \hat{s}_\theta(\mathbf{x}) - \nabla_\mathbf{x} \log p(\mathbf{x}) \right)^2 .\]In this form however, this loss function is not practical, because we do not have a good way to compute ground truth scores \(\nabla_\mathbf{x} \log p(\mathbf{x})\) for any data point \(\mathbf{x}\). There are a few tricks that can be applied to sidestep this requirement, and transform this into a loss function that’s easy to compute, including implicit score matching (ISM)6, sliced score matching (SSM)7 and denoising score matching (DSM)8. We’ll take a closer look at this last one:

\[\mathcal{L}_{DSM} := \left( \hat{s}_\theta(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}) - \nabla_\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \log p(\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \mid \mathbf{x}) \right)^2 .\]Here, \(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}\) is obtained by adding Gaussian noise to \(\mathbf{x}\). This means \(p(\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \mid \mathbf{x})\) is distributed according to a Gaussian distribution \(\mathcal{N}\left(\mathbf{x}, \sigma^2\right)\) and the ground truth conditional score function can be calculated in closed form:

\[\nabla_\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \log p(\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \mid \mathbf{x}) = \nabla_\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \log \left( \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{ -\frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{\tilde{\mathbf{x}} - \mathbf{x}}{\sigma} \right)^2 } \right)\] \[= \nabla_\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \log \frac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2 \pi}} - \nabla_\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \left( \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{\tilde{\mathbf{x}} - \mathbf{x}}{\sigma} \right)^2 \right) = 0 - \frac{1}{2} \cdot 2 \left( \frac{\tilde{\mathbf{x}} - \mathbf{x}}{\sigma} \right) \cdot \frac{1}{\sigma} = \frac{\mathbf{x} - \tilde{\mathbf{x}}}{\sigma^2}.\]This form has a very intuitive interpretation: it is a scaled version of the Gaussian noise added to \(\mathbf{x}\) to obtain \(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}\). Therefore, making \(\tilde{\mathbf{x}}\) more likely by following the score (= gradient ascent on the log-likelihood) directly corresponds to removing (some of) the noise:

\[\tilde{\mathbf{x}} + \eta \cdot \nabla_\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \log p(\tilde{\mathbf{x}} \mid \mathbf{x}) = \tilde{\mathbf{x}} + \frac{\eta}{\sigma^2} \left(\mathbf{x} - \tilde{\mathbf{x}}\right) = \frac{\eta}{\sigma^2} \mathbf{x} + \left(1 - \frac{\eta}{\sigma^2}\right) \tilde{\mathbf{x}} .\]If we choose the step size \(\eta = \sigma^2\), we recover the clean data \(\mathbf{x}\) in a single step.

\(\mathcal{L}_{SM}\) and \(\mathcal{L}_{DSM}\) are different loss functions, but the neat thing is that they have the same minimum in expectation: \(\mathbb{E}_\mathbf{x} [\mathcal{L}_{SM}] = \mathbb{E}_{\mathbf{x},\tilde{\mathbf{x}}} [\mathcal{L}_{DSM}] + C\), where \(C\) is some constant. Pascal Vincent derived this equivalence back in 2010 (before score matching was cool!) and I strongly recommend reading his tech report about it8 if you want to deepen your understanding.

One important question this approach raises is: how much noise should we add, i.e. what should \(\sigma\) be? Picking a particular fixed value for this hyperparameter doesn’t actually work very well in practice. At low noise levels, it is very difficult to estimate the score accurately in low-density regions. At high noise levels, this is less of a problem, because the added noise spreads out the density in all directions – but then the distribution that we’re modelling is significantly distorted by the noise. What works well is to model the density at many different noise levels. Once we have such a model, we can anneal \(\sigma\) during sampling, starting with lots of noise and gradually dialing it down. Song & Ermon describe these issues and their elegant solution in detail in their 2019 paper9.

This combination of denoising score matching at many different noise levels with gradual annealing of the noise during sampling yields a model that’s essentially equivalent to a DDPM, but the derivation is completely different – no ELBOs in sight! To learn more about this perspective, check out Yang Song’s excellent blog post on the topic.

Diffusion models solve reverse SDEs

In both of the previous perspectives (deep latent variable models and score matching), we consider a discete and finite set of steps. These steps correspond to different levels of Gaussian noise, and we can write down a monotonic mapping \(\sigma(t)\) which maps the step index \(t\) to the standard deviation of the noise at that step.

If we let the number of steps go to infinity, it makes sense to replace the discrete index variable with a continuous value \(t\) on an interval \([0, T]\), which can be interpreted as a time variable, i.e. \(\sigma(t)\) now describes the evolution of the standard deviation of the noise over time. In continuous time, we can describe the diffusion process which gradually adds noise to data points \(\mathbf{x}\) with a stochastic differential equation (SDE):

\[\mathrm{d} \mathbf{x} = \mathbf{f}(\mathbf{x}, t) \mathrm{d}t + g(t) \mathrm{d} \mathbf{w} .\]This equation relates an infinitesimal change in \(\mathbf{x}\) with an infintesimal change in \(t\), and \(\mathrm{d}\mathbf{w}\) represents infinitesimal Gaussian noise, also known as the Wiener process. \(\mathbf{f}\) and \(g\) are called the drift and diffusion coefficients respectively. Particular choices for \(\mathbf{f}\) and \(g\) yield time-continuous versions of the Markov chains used to formulate DDPMs.

SDEs combine differential equations with stochastic random variables, which can seem a bit daunting at first. Luckily we don’t need too much of the advanced SDE machinery that exists to understand how this perspective can be useful for diffusion models. However, there is one very important result that we can make use of. Given an SDE that describes a diffusion process like the one above, we can write down another SDE that describes the process in the other direction, i.e. reverses time10:

\[\mathrm{d}\mathbf{x} = \left(\mathbf{f}(\mathbf{x}, t) - g(t)^2 \nabla_\mathbf{x} \log p_t(\mathbf{x}) \right) \mathrm{d}t + g(t) \mathrm{d} \bar{\mathbf{w}} .\]This equation also describes a diffusion process. \(\mathrm{d}\bar{\mathbf{w}}\) is the reversed Wiener process, and \(\nabla_\mathbf{x} \log p_t(\mathbf{x})\) is the time-dependent score function. The time dependence comes from the fact that the noise level changes over time.

Explaining why this is the case is beyond the scope of this blog post, but the original paper by Yang Song and colleagues that introduced the SDE-based formalism for diffusion models11 is well worth a read.

Concretely, if we have a way to estimate the time-dependent score function, we can simulate the reverse diffusion process, and therefore draw samples from the data distribution starting from noise. So we can once again train a neural network to predict this quantity, and plug it into the reverse SDE to obtain a continuous-time diffusion model.

In practice, simulating this SDE requires discretising the time variable \(t\) again, so you might wonder what the point of all this is. What’s neat is that this discretisation is now something we can decide at sampling-time, and it does not have to be fixed before we train our score prediction model. In other words, we can trade off sample quality for computational cost in a very natural way without changing the model, by choosing the number of sampling steps.

Diffusion models are flow-based models

Remember flow-based models12 13? They aren’t very popular for generative modelling these days, which I think is mainly because they tend to require more parameters than other types of models to achieve the same level of performance. This is due to their limited expressivity: neural networks used in flow-based models are required to be invertible, and the log-determinant of the Jacobian must be easy to compute, which imposes significant constraints on the kinds of computations that are possible.

At least, this is the case for discrete normalising flows. Continuous normalising flows (CNFs)14 15 also exist, and usually take the form of an ordinary differential equation (ODE) parameterised by a neural network, which describes a deterministic path between samples from the data distribution and corresponding samples from a simple base distribution (e.g. standard Gaussian). CNFs are not affected by the aforementioned neural network architecture constraints, but in their original form, they require backpropagation through an ODE solver to train. Although some tricks exist to do this more efficiently, this probably also presents a barrier to widespread adoption.

Let’s revisit the SDE formulation of diffusion models, which describes a stochastic process mapping samples from a simple base distribution to samples from the data distribution. An interesting question to ask is: what does the distribution of the intermediate samples \(p_t(\mathbf{x})\) look like, and how does it evolve over time? This is governed by the so-called Fokker-Planck equation. If you want to see what this looks like in practice, check out appendix D.1 of Song et al. (2021)11.

Here’s where it gets wild: there exists an ODE that describes a deterministic process whose time-dependent distributions are exactly the same as those of the stochastic process described by the SDE. This is called the probability flow ODE. What’s more, it has a simple closed form:

\[\mathrm{d} \mathbf{x} = \left( \mathbf{f}(\mathbf{x}, t) - \frac{1}{2}g(t)^2 \nabla_\mathbf{x} \log p_t(\mathbf{x}) \right)\mathrm{d}t .\]This equation describes both the forward and backward process (just flip the sign to go in the other direction), and note that the time-dependent score function \(\nabla_\mathbf{x} \log p_t(\mathbf{x})\) once again features. To prove this, you can write down the Fokker-Planck equations for both the SDE and the probability flow ODE, and do some algebra to show that they are the same, and hence must have the same solution \(p_t(\mathbf{x})\).

Note that this ODE does not describe the same process as the SDE: that would be impossible, because a deterministic differential equation cannot describe a stochastic process. Instead, it describes a different process with the unique property that the distributions \(p_t(\mathbf{x})\) are the same for both processes. Check out the probability flow ODE section in Yang Song’s blog post for a great diagram comparing both processes.

The implications of this are profound: there is now a bijective mapping between particular samples from the simple base distribution, and samples from the data distribution. We have a sampling process where all the randomness is contained in the initial base distribution sample – once that’s been sampled, going from there to a data sample is completely deterministic. It also means that we can map data points to their corresponding latent representations by simulating the ODE forward, manipulating them, and then mapping them back to the data space by simulating the ODE backward.

The model described by the probability flow ODE is a continuous normalising flow, but it’s one that we managed to train without having to backpropagate through an ODE, rendering the approach much more scalable.

The fact that all this is possible, without even changing anything about how the model is trained, still feels like magic to me. We can plug our score predictor into the reverse SDE from the previous section, or the ODE from this one, and get out two different generative models that model the same distribution in different ways. How cool is that?

As a bonus, the probability flow ODE also enables likelihood computation for diffusion models (see appendix D.2 of Song et al. (2021)11). This also requires solving the ODE, so it’s roughly as expensive as sampling.

For all of the reasons above, the probability flow ODE paradigm has proven quite popular recently. Among other examples, it is used by Karras et al.16 as a basis for their work investigating various diffusion modelling design choices, and my colleagues and I recently used it for our work on diffusion language models17. It has also been generalised and extended beyond diffusion processes, to enable learning a mapping between any pair of distributions, e.g. in the form of Flow Matching18, Rectified Flows19 and Stochastic Interpolants20.

Side note: another way to obtain a deterministic sampling process for diffusion models is given by DDIM21, which is based on the deep latent variable model perspective.

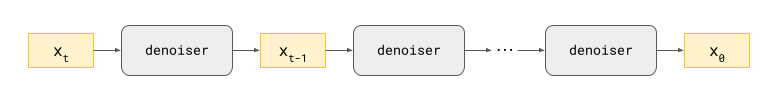

Diffusion models are recurrent neural networks (RNNs)

Sampling from a diffusion model involves making repeated predictions with a neural network and using those predictions to update a canvas, which starts out filled with random noise. If we consider the full computational graph of this process, it starts to look a lot like a recurrent neural network (RNN). In RNNs, there is a hidden state which repeatedly gets updated by passing it through a recurrent cell, which consists of one or more nonlinear parameterised operations (e.g. the gating mechanisms of LSTMs22). Here, the hidden state is the canvas, so it lives in the input space, and the cell is formed by the denoiser neural network that we’ve trained for our diffusion model.

RNNs are usually trained with backpropagation through time (BPTT), with gradients propagated through the recurrence. The number of recurrent steps to backpropagate through is often limited to some maximum number to reduce the computational cost, which is referred to as truncated BPTT. Diffusion models are also trained by backpropagation, but only through one step at a time. In some sense, diffusion models present a way to train deep recurrent neural networks without backpropagating through the recurrence at all, yielding a much more scalable training procedure.

RNNs are usually deterministic, so this analogy makes the most sense for the deterministic process based on the probability flow ODE described in the previous section – though injecting noise into the hidden state of RNNs as a means of regularisation is not unheard of, so I think the analogy also works for the stochastic process.

The total depth of this computation graph in terms of the number of nonlinear layers is given by the number of layers in our neural network, multiplied by the number of sampling steps. We can look at the unrolled recurrence as a very deep neural network in its own right, with potentially thousands of layers. This is a lot of depth, but it stands to reason that a challenging task like generative modelling of real-world data requires such deep computation graphs.

We can also consider what happens if we do not use the same neural network at each diffusion sampling step, but potentially different ones for different ranges of noise levels. These networks can be trained separately and independently, and can even have different architectures. This means we are effectively “untying the weights” in our very deep network, turning it from an RNN into a plain old deep neural network, but we are still able to avoid having to backpropagate through all of it in one go. Stable Diffusion XL23 uses this approach to great effect for its “Refiner” model, so I think it might start to catch on.

When I started my PhD in 2010, training neural networks with more than two hidden layers was a chore: backprop didn’t work well out of the box, so we used unsupervised layer-wise pre-training1 24 to find a good initialisation which would make backpropagation possible. Nowadays, even hundreds of nonlinear layers do not form an obstacle anymore. Therefore it’s not inconceivable that several years from now, training networks with tens of thousands of layers by backprop will be within reach. At that point, the “divide and conquer” approach that diffusion models offer might lose its luster, and perhaps we’ll all go back to training deep variational autoencoders! (Note that the same “divide and conquer” perspective equally applies to autoregressive models, so they would become obsolete as well, in that case.)

One question this perspective raises is whether diffusion models might actually work better if we backpropagated through the sampling procedure for two or more steps. This approach isn’t popular, which probably indicates that it isn’t cost-effective in practice. There is one important exception (sort of): models which use self-conditioning25, such as Recurrent Interface Networks (RINs)26, pass some form of state between the diffusion sampling steps, in addition to the updated canvas. To enable the model to learn to make use of this state, an approximation of it is made available during training by running an additional forward pass. There is no additional backward pass though, so this doesn’t really count as two steps of BPTT – more like 1.5 steps.

Diffusion models are autoregressive models

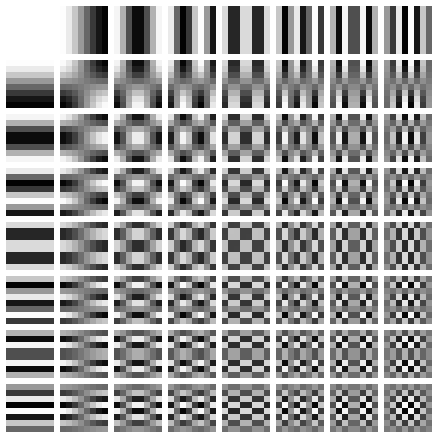

For diffusion models of natural images, the sampling process tends to produce large-scale structure first, and then iteratively adds more and more fine-grained details. Indeed, there seems to be almost a direct correspondence between noise levels and feature scales, which I discussed in more detail in Section 5 of a previous blog post.

But why is this the case? To understand this, it helps to think in terms of spatial frequencies. Large-scale features in images correspond to low spatial frequencies, whereas fine-grained details correspond to high frequencies. We can decompose images into their spatial frequency components using the 2D Fourier transform (or some variant of it). This is often the first step in image compression algorithms, because the human visual system is known to be much less sensitive to high frequencies, and this can be exploited by compressing them more aggressively than low frequencies.

Natural images, along with many other natural signals, exhibit an interesting phenomenon in the frequency domain: the magnitude of different frequency components tends to drop off proportionally to the inverse of the frequency27: \(S(f) \propto 1/f\) (or the inverse of the square of the frequency, if you’re looking at power spectra instead of magnitude spectra).

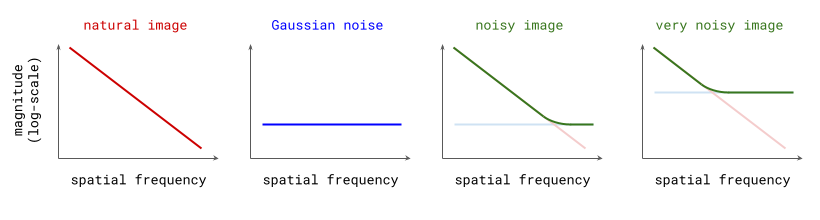

Gaussian noise, on the other hand, has a flat spectrum: in expectation, all frequencies have the same magnitude. Since the Fourier transform is a linear operation, adding Gaussian noise to a natural image yields a new image whose spectrum is the sum of the spectrum of the original image, and the flat spectrum of the noise. In the log-domain, this superposition of the two spectra looks like a hinge, which shows how the addition of noise obscures any structure present in higher spatial frequencies (see figure below). The larger the standard deviation of this noise, the more spatial frequencies will be affected.

Since diffusion models are constructed by progressively adding more noise to input examples, we can say that this process increasingly drowns out lower and lower frequency content, until all structure is erased (for natural images, at least). When sampling from the model, we go in the opposite direction and effectively add structure at higher and higher spatial frequencies. This basically looks like autoregression, but in frequency space! Rissanen et al. (2023) discuss this observation in Section 2.2 of their paper28 on generative modelling with inverse heat dissipation (as an alternative to Gaussian diffusion), though they do not make the connection to autoregressive models. I added that bit, so this section could have a provocative title.

An important caveat is that this interpretation relies on the frequency characteristics of natural signals, so for applications of diffusion models in other domains (e.g. language modelling, see Section 2 of my blog post on diffusion language models), the analogy may not make sense.

Diffusion models estimate expectations

Consider the transition density \(p(\mathbf{x}_t \mid \mathbf{x}_0)\), which describes the distribution of the noisy data example \(\mathbf{x}_t\) at time \(t\), conditioned on the original clean input \(\mathbf{x}_0\) it was derived from (by adding noise). Based on samples from this distribution, the neural network used in a diffusion model is tasked to predict the expectation \(\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_t]\) (or some linear time-dependent function of it). This may seem a tad obvious, but I wanted to highlight some of the implications.

First, it provides another motivation for why the mean squared error (MSE) is the right loss function to use for training diffusion models. During training, the expectation \(\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_t]\) is not known, so instead we supervise the model using \(\mathbf{x}_0\) itself. Because the minimiser of the MSE loss is precisely the expectation, we end up recovering (an approximation of) \(\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_t]\), even though we don’t know this quantity a priori. This is a bit different from typical supervised learning problems, where the ideal outcome would be for the model to predict exactly the targets used to supervise it (barring any label errors). Here, we purposely do not want that. More generally, the notion of being able to estimate conditional expectations, even though we only provide supervision through samples, is very powerful.

Second, it explains why distillation29 of diffusion models30 31 32 is such a compelling proposition: in this setting, we are able to supervise a diffusion model directly with an approximation of the target expectation \(\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_t]\) that we want it to predict, because that is what the teacher model already provides. As a result, the variance of the training loss will be much lower than if we had trained the model from scratch, and convergence will be much faster. Of course, this is only useful if you already have a trained model on hand to use as a teacher.

Discrete and continuous diffusion models

So far, we have covered several perspectives that consider a finite set of discrete noise levels, and several perspectives that use a notion of continuous time, combined with a mapping function \(\sigma(t)\) to map time steps to the corresponding standard deviation of the noise. These are typically referred to as discrete-time and continuous-time respectively. One thing that’s quite neat is that this is mostly a matter of interpretation: models trained within a discrete-time perspective can usually be repurposed quite easily to work in the continuous-time setting16, and vice versa.

Another way in which diffusion models can be discrete or continuous, is with respect to the input space. In the literature, I’ve found that it is sometimes unclear whether “continuous” or “discrete” are meant to be with respect to time, or with respect to the input. This is especially important because some perspectives only really make sense for continuous input, as they rely on gradients with respect to the input (i.e. all perspectives based on the score function).

All four combinations of discreteness/continuity exist:

- discrete time, continuous input: the original deep latent variable model perspective (DDPMs), as well as the score-based perspective;

- continuous time, continuous input: SDE- and ODE-based perspectives;

- discrete time, discrete input: D3PM33, MaskGIT34, Mask-predict35, ARDM36, Multinomial diffusion37 and SUNDAE38 are all methods that use iterative refinement on discrete inputs – whether all of these should be considered diffusion models isn’t entirely clear (it depends on who you ask);

- continuous time, discrete input: Continuous Time Markov Chains (CTMCs)39, Score-based Continuous-time Discrete Diffusion Models40 and Blackout Diffusion41 all pair discrete input with continuous time – this setting is also often handled by embedding discrete data in Euclidean space, and then performing input-continuous diffusion in that space, as in e.g. Analog Bits25, Self-conditioned Embedding Diffusion42 and CDCD17.

Alternative formulations

Recently, a few papers have proposed new derivations of this class of models from first principles with the benefit of hindsight, avoiding concepts such as differential equations, ELBOs or score matching altogether. These works provide yet another perspective on diffusion models, which may be more accessible because it requires less background knowledge.

Inversion by Direct Iteration (InDI)43 is a formulation rooted in image restoration, intended to harness iterative refinement to improve perceptual quality. No assumptions are made about the nature of the image degradations, and models are trained on paired low-quality and high-quality examples. Iterative \(\alpha\)-(de)blending44 uses linear interpolation between samples from two different distributions as a starting point to obtain a deterministic mapping between the distributions. Both of these methods are also closely related to Flow Matching18, Rectified Flow19 and Stochastic Interpolants20 discussed earlier.

Consistency

A few different notions of “consistency” in diffusion models have arisen in literature recently:

-

Consistency models (CM)45 are trained to map points on any trajectory of the probability flow ODE to the trajectory’s origin (i.e. the clean data point), enabling sampling in a single step. This is done indirectly by taking pairs of points on a particular trajectory and ensuring that the model output is the same for both (hence “consistency”). There is a distillation variant which starts from an existing diffusion model, but it is also possible to train a consistency model from scratch.

-

Consistent diffusion models (CDM)46 are trained using a regularisation term that explicitly encourages consistency, which they define to mean that the prediction of the denoiser should correspond to the conditional expectation \(\mathbb{E}[\mathbf{x}_0 \mid \mathbf{x}_t]\) (see earlier).

-

FP-Diffusion47 takes the Fokker-Planck equation describing the evolution across time of \(p_t(\mathbf{x})\), and introduces an explicit regularisation term to ensure that it holds.

Each of these properties would trivially hold for an ideal diffusion model (i.e. fully converged, in the limit of infinite capacity). However, real diffusion models are approximate, and so they tend not to hold in practice, which is why it makes sense to add mechanisms to explicitly enforce them.

The main reason for including this section here is that I wanted to highlight a recent paper by Lai et al. (2023)48 that shows that these three different notions of consistency are essentially different perspectives on the same thing. I thought this was a very elegant result, and it definitely suits the theme of this blog post!

Defying conventions

Apart from all these different perspectives on a conceptual level, the diffusion literature is also particularly fraught in terms of reinventing notation and defying conventions, in my experience. Sometimes, even two different descriptions of the same conceptual perspective look nothing alike. This doesn’t help accessibility and increases the barrier to entry. (I’m not blaming anyone for this, to be clear – in fact, I suspect I might be contributing to the problem with this blog post. Sorry about that.)

There are also a few other seemingly innocuous details and parameterisation choices that can have profound implications. Here are three things to watch out for:

-

By and large, people use variance-preserving (VP) diffusion processes, where in addition to adding noise at each step, the current canvas is rescaled to preserve the overall variance. However, the variance-exploding (VE) formulation, where no rescaling happens and the variance of the added noise increases towards infinity, has also gained some followers. Most notably it is used by Karras et al. (2022)16. Some results that hold for VP diffusion might not hold for VE diffusion or vice versa (without making the requisite changes), and this might not be mentioned explicitly. If you’re reading a diffusion paper, make sure you are aware of which formulation is used, and whether any assumptions are being made about it.

-

Sometimes, the neural network used in a diffusion model is parameterised to predict the (standardised) noise added to the input, or the score function; sometimes it predicts the clean input instead, or even a time-dependent combination of the two (as in e.g. \(\mathbf{v}\)-prediction30). All of these targets are equivalent in the sense that they are time-dependent linear functions of each other and the noisy input \(\mathbf{x}_t\). But it is important to understand how this interacts with the relative weighting of loss contributions for different time steps during training, which can significantly affect model performance. Out of the box, predicting the standardised noise seems to be a great choice for image data. When modelling certain other quantities (e.g. latents in latent diffusion), people have found predicting the clean input to work better. This is primarily because it implies a different weighting of noise levels, and hence feature scales.

-

It is generally understood that the standard deviation of the noise added by the corruption process increases with time, i.e. entropy increases over time, as it tends to do in our universe. Therefore, \(\mathbf{x}_0\) corresponds to clean data, and \(\mathbf{x}_T\) (for some large enough \(T\)) corresponds to pure noise. Some works (e.g. Flow Matching18) invert this convention, which can be very confusing if you don’t notice it straight away.

Finally, it’s worth noting that the definition of “diffusion” in the context of generative modelling has grown to be quite broad, and is now almost equivalent to “iterative refinement”. A lot of “diffusion models” for discrete input are not actually based on diffusion processes, but they are of course closely related, so the scope of this label has gradually been extended to include them. It’s not clear where to draw the line: if any model which implements iterative refinement through inversion of a gradual corruption process is a diffusion model, then all autoregressive models are also diffusion models. To me, that seems confusing enough so as to render the term useless.

Closing thoughts

Learning about diffusion models right now must be a pretty confusing experience, but the exploration of all these different perspectives has resulted in a diverse toolbox of methods which can all be combined together, because ultimately, the underlying model is always the same. I’ve also found that learning about how the different perspectives relate to each other has considerably deepened my understanding. Some things that are a mystery from one perspective are clear as day in another.

If you are just getting started with diffusion, hopefully this post will help guide you towards the right things to learn next. If you are a seasoned diffuser, I hope I’ve broadened your perspectives and I hope you’ve learnt something new nevertheless. Thanks for reading!

What's your favourite perspective on diffusion? Are there any useful perspectives that I've missed? Please share your thoughts in the comments below, or reach out on Twitter (@sedielem) or Threads (@sanderdieleman) if you prefer. Email is okay too.

I will also be at ICML 2023 in Honolulu and would be happy to chat in person!

If you would like to cite this post in an academic context, you can use this BibTeX snippet:

@misc{dieleman2023perspectives,

author = {Dieleman, Sander},

title = {Perspectives on diffusion},

url = {https://sander.ai/2023/07/20/perspectives.html},

year = {2023}

}

Acknowledgements

Thanks to my colleagues at Google DeepMind for various discussions, which continue to shape my thoughts on this topic! Thanks to Ayan Das, Ira Korshunova, Peyman Milanfar, and Çağlar Ünlü for suggestions and corrections.

References

-

Bengio, Lamblin, Popovici, Larochelle, “Greedy Layer-Wise Training of Deep Networks”, Neural Information Processing Systems, 2006. ↩ ↩2

-

Sohl-Dickstein, Weiss, Maheswaranathan, Ganguli, “Deep Unsupervised Learning using Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics”, International Conference on Machine Learning, 2015. ↩

-

Ho, Jain, Abbeel, “Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models”, 2020. ↩

-

Kingma and Welling, “Auto-Encoding Variational Bayes”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2014. ↩

-

Rezende, Mohamed and Wierstra, “Stochastic Backpropagation and Approximate Inference in Deep Generative Models”, International Conference on Machine Learning, 2014. ↩

-

Hyvärinen, “Estimation of Non-Normalized Statistical Models by Score Matching”, Journal of Machine Learning Research, 2005. ↩ ↩2

-

Song, Garg, Shi, Ermon, “Sliced Score Matching: A Scalable Approach to Density and Score Estimation”, Uncertainty in Artifical Intelligence, 2019. ↩

-

Vincent, “A Connection Between Score Matching and Denoising Autoencoders”, Technical report, 2010. ↩ ↩2

-

Song, Ermon, “Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution”, Neural Information Processing Systems, 2019. ↩

-

Anderson, “Reverse-time diffusion equation models”, Stochastic Processes and their Applications, 1982. ↩

-

Song, Sohl-Dickstein, Kingma, Kumar, Ermon and Poole, “Score-Based Generative Modeling through Stochastic Differential Equations”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Dinh, Krueger, Bengio, “NICE: Non-linear Independent Components Estimation”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2015. ↩

-

Dinh, Sohl-Dickstein, Bengio, “Density estimation using Real NVP”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2017. ↩

-

Chen, Rubanova, Bettencourt, Duvenaud, “Neural Ordinary Differential Equations”, Neural Information Processing Systems, 2018. ↩

-

Grathwohl, Chen, Bettencourt, Sutskever, Duvenaud, “FFJORD: Free-form Continuous Dynamics for Scalable Reversible Generative Models”, Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018. ↩

-

Karras, Aittala, Aila, Laine, “Elucidating the Design Space of Diffusion-Based Generative Models”, Neural Information Processing Systems, 2022. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Dieleman, Sartran, Roshannai, Savinov, Ganin, Richemond, Doucet, Strudel, Dyer, Durkan, Hawthorne, Leblond, Grathwohl, Adler, “Continuous diffusion for categorical data”, arXiv, 2022. ↩ ↩2

-

Lipman, Chen, Ben-Hamu, Nickel, Le, “Flow Matching for Generative Modeling”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Liu, Gong, Liu, “Flow Straight and Fast: Learning to Generate and Transfer Data with Rectified Flow”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Albergo, Vanden-Eijnden, “Building Normalizing Flows with Stochastic Interpolants”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Song, Meng, Ermon, “Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021. ↩

-

Hochreiter, Schmidhuber, “Long short-term memory”, Neural Computation, 1997. ↩

-

Podell, English, Lacey, Blattmann, Dockhorn, Muller, Penna, Rombach, “SDXL: Improving Latent Diffusion Models for High-Resolution Image Synthesis”, tech report, 2023. ↩

-

Hinton, Osindero, Teh, “A Fast Learning Algorithm for Deep Belief Nets”, Neural Computation, 2006. ↩

-

Chen, Zhang, Hinton, “Analog Bits: Generating Discrete Data using Diffusion Models with Self-Conditioning”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Jabri, Fleet, Chen, “Scalable Adaptive Computation for Iterative Generation”, arXiv, 2022. ↩

-

Torralba, Oliva, “Statistics of Natural Image Categories”, Network: Computation in Neural Systems, 2003. ↩

-

Rissanen, Heinonen, Solin, “Generative Modelling With Inverse Heat Dissipation”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023. ↩

-

Hinton, Vinyals, Dean, “Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network”, Neural Information Processing Systems, Deep Learning and Representation Learning Workshop, 2015. ↩

-

Salimans, Ho, “Progressive Distillation for Fast Sampling of Diffusion Models”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022. ↩ ↩2

-

Meng, Rombach, Gao, Kingma, Ermon, Ho, Salimans, “On Distillation of Guided Diffusion Models”, Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2023. ↩

-

Berthelot, Autef, Lin, Yap, Zhai, Hu, Zheng, Talbott, Gu, “TRACT: Denoising Diffusion Models with Transitive Closure Time-Distillation”, arXiv, 2023. ↩

-

Austin, Johnson, Ho, Tarlow, van den Berg, “Structured Denoising Diffusion Models in Discrete State-Spaces”, Neural Information Processing Systems, 2021. ↩

-

Chang, Zhang, Jiang, Liu, Freeman, “MaskGIT: Masked Generative Image Transformer”, Computer Vision and Patern Recognition, 2022. ↩

-

Ghazvininejad, Levy, Liu, Zettlemoyer, “Mask-Predict: Parallel Decoding of Conditional Masked Language Models”, Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, 2019. ↩

-

Hoogeboom, Gritsenko, Bastings, Poole, van den Berg, Salimans, “Autoregressive Diffusion Models”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022. ↩

-

Hoogeboom, Nielsen, Jaini, Forré, Welling, “Argmax Flows and Multinomial Diffusion: Learning Categorical Distributions”, Neural Information Processing Systems, 2021. ↩

-

Savinov, Chung, Binkowski, Elsen, van den Oord, “Step-unrolled Denoising Autoencoders for Text Generation”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2022. ↩

-

Campbell, Benton, De Bortoli, Rainforth, Deligiannidis, Doucet, “A continuous time framework for discrete denoising models”, Neural Information Processing Systems, 2022. ↩

-

Sun, Yu, Dai, Schuurmans, Dai, “Score-based Continuous-time Discrete Diffusion Models”, International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023. ↩

-

Santos, Fox, Lubbers, Lin, “Blackout Diffusion: Generative Diffusion Models in Discrete-State Spaces”, International Conference on Machine Learning, 2023. ↩

-

Strudel, Tallec, Altché, Du, Ganin, Mensch, Grathwohl, Savinov, Dieleman, Sifre, Leblond, “Self-conditioned Embedding Diffusion for Text Generation”, arXiv, 2022. ↩

-

Delbracio, Milanfar, “Inversion by Direct Iteration: An Alternative to Denoising Diffusion for Image Restoration”, Transactions on Machine Learning Research, 2023. ↩

-

Heitz, Belcour, Chambon, “Iterative alpha-(de)Blending: a Minimalist Deterministic Diffusion Model”, SIGGRAPH 2023. ↩

-

Song, Dhariwal, Chen, Sutskever, “Consistency Models”, International Conference on Machine Learning, 2023. ↩

-

Daras, Dagan, Dimakis, Daskalakis, “Consistent Diffusion Models: Mitigating Sampling Drift by Learning to be Consistent”, arXiv, 2023. ↩

-

Lai, Takida, Murata, Uesaka, Mitsufuji, Ermon, “FP-Diffusion: Improving Score-based Diffusion Models by Enforcing the Underlying Score Fokker-Planck Equation”, International Conference on Machine Learning, 2023. ↩

-

Lai, Takida, Uesaka, Murata, Mitsufuji, Ermon, “On the Equivalence of Consistency-Type Models: Consistency Models, Consistent Diffusion Models, and Fokker-Planck Regularization”, arXiv, 2023. ↩